Timing the Shield: How I Learned to Hedge Without the Heartburn

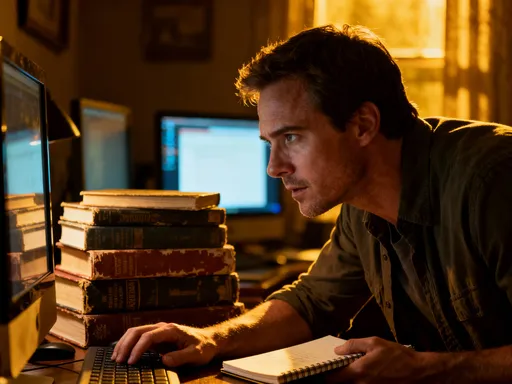

Everyone talks about making money, but few talk about keeping it when the market turns. I learned this the hard way—after jumping into hedges at the wrong moment and watching my buffer become a burden. Risk protection shouldn’t add more risk. Through trial, error, and real-world testing, I discovered that timing isn’t just important in hedging—it’s everything. Let me walk you through what actually works when the pressure’s on.

The Trap of Reactive Hedging

Most investors approach hedging like an insurance policy they only buy after the accident has already happened. They wait for the red alerts, the plunging headlines, the sudden 5% drop in their portfolio before scrambling to protect what’s left. But by then, the damage is often already done. This reactive mindset transforms what should be a strategic defense into a costly and emotionally charged maneuver. When fear drives the decision, logic tends to take a back seat. Investors may overpay for options, lock in unfavorable positions, or misapply complex instruments they don’t fully understand—all in a rush to feel safe again.

The financial cost of delayed action is often matched by psychological strain. Consider the scenario of a sudden market correction triggered by geopolitical tension or inflation data. An investor who waits until the downturn is in full swing might pay significantly more for put options than they would have during calmer periods. Volatility, measured by indicators like the VIX, tends to spike precisely when protection is most desired, making hedging tools more expensive. What’s more, emotional decisions often lead to inconsistent strategies. One month, an investor might load up on gold as a safe haven; the next, they could switch to shorting equities—without a coherent plan. This lack of structure undermines the very purpose of risk management.

Another danger of reactive hedging is the illusion of control. After taking a protective position during a crisis, investors may feel they’ve neutralized risk, when in reality, they’ve only shifted it. For example, buying inverse ETFs to hedge a stock portfolio sounds logical, but these instruments are designed for short-term use and can decay in value over time due to compounding effects. Holding them through a prolonged downturn may result in losses on both sides—equities fall, and the hedge erodes. The lesson is clear: waiting for trouble before acting doesn’t protect wealth; it often compounds the problem.

Moreover, timing delays can lead to missed opportunities. When investors react late, they may exit positions at the worst possible moment, locking in losses and missing the early stages of recovery. Markets often rebound sharply after a panic, sometimes within days. A hedge put in place too late might prevent further losses, but it won’t help recoup what’s already gone. The better approach is not to chase safety after the storm, but to prepare for it before the clouds gather.

What Hedging Really Means (Beyond the Hype)

Hedging is frequently misunderstood as a way to eliminate risk entirely, but that’s neither possible nor practical. True hedging is about managing exposure, not erasing it. It’s the financial equivalent of wearing a seatbelt—not a guarantee against injury, but a measured step to reduce potential harm. The goal isn’t to profit from the hedge itself, but to limit downside when the unexpected occurs. This distinction is crucial. Many investors confuse hedging with speculation, using tools like options or futures not to protect, but to bet against the market. When that happens, the strategy stops being a shield and starts being a second gamble.

A genuine hedge aligns with the structure and objectives of the underlying portfolio. For instance, an investor holding a diversified mix of U.S. large-cap stocks might use S&P 500 put options to cap potential losses during periods of elevated uncertainty. The intention here is not to gain from market declines, but to ensure that a sharp drop doesn’t derail long-term financial goals. Similarly, someone with international investments might hedge currency risk by using forward contracts or currency-hedged ETFs. Again, the purpose is stability, not profit. The value of such strategies reveals itself not in gains, but in preserved capital when markets turn volatile.

Another effective form of hedging is diversification across asset classes that behave differently under stress. For example, bonds have historically moved inversely to stocks during market shocks, providing a natural cushion. Real assets like gold or real estate can also serve as hedges against inflation, which often undermines the purchasing power of fixed-income investments. These are not speculative bets; they are deliberate allocations designed to smooth out portfolio volatility over time. The key is correlation—or lack thereof. Assets that don’t move in lockstep reduce overall risk without requiring constant intervention.

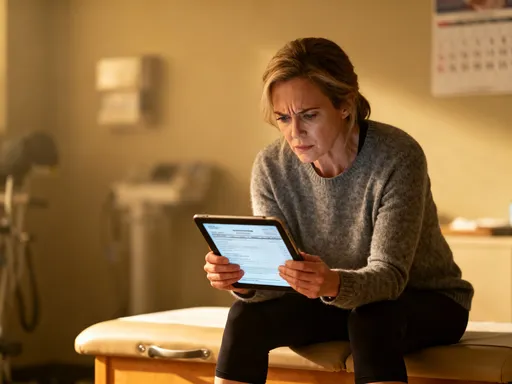

It’s also important to recognize that hedging comes at a cost. Whether it’s the premium paid for an option, the management fee on a hedged ETF, or the opportunity cost of holding cash, there’s always a trade-off. This cost is the price of insurance, much like paying a monthly premium for homeowners coverage. The wise investor accepts this cost as part of responsible stewardship, not as a burden to be avoided. The discipline lies in ensuring that the cost is proportional to the risk being managed—no more, no less.

Why Timing Makes or Breaks Your Hedge

No hedge, no matter how well-structured, can succeed if deployed at the wrong time. Timing determines not only effectiveness but also efficiency. A hedge entered too early may drain resources through ongoing costs without ever being needed, while one entered too late may arrive after the worst damage has already occurred. The ideal window for protection lies in the period before volatility erupts, when insurance is still affordable and strategic positioning is possible. This requires foresight, not reaction.

Market cycles play a significant role in timing. During extended bull markets, complacency sets in. Investors grow accustomed to steady gains and begin to view risk as remote. In such environments, the cost of hedging—such as option premiums—tends to be low because demand for protection is minimal. This is often the best time to establish defensive positions, even if the immediate threat isn’t visible. Waiting until fear returns means paying higher prices for the same protection, reducing its value.

Sentiment extremes also signal critical timing opportunities. When investor optimism reaches euphoric levels—measured by surveys, margin debt, or IPO activity—it often precedes a correction. Conversely, when pessimism peaks, markets may already be pricing in the worst-case scenario, making aggressive hedging unnecessary or even counterproductive. The most effective hedges are put in place when conditions are still stable but showing early signs of strain, allowing investors to act from a position of strength rather than desperation.

Asset valuations further influence timing. When equity markets trade at historically high price-to-earnings ratios, the potential for downside increases. At such times, even moderate economic setbacks can trigger outsized reactions. A disciplined investor might respond by gradually increasing their hedge exposure, not all at once, but in measured steps as valuations stretch further. This approach avoids the risk of mistiming the market while still acknowledging rising vulnerability. The goal is not to predict the exact moment of a downturn, but to be prudently prepared when it arrives.

Recognizing the Right Signals (Not Just the Obvious Ones)

While headlines capture attention, the most reliable signals for hedging often come from less dramatic sources. These are the quiet warnings that precede market shifts—indicators that don’t make the evening news but matter deeply to those who monitor them. One of the most telling is a sustained rise in market volatility, often reflected in the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX). When the VIX begins to trend upward after a prolonged period of calm, it suggests that uncertainty is growing, even if prices haven’t yet reacted. This can be an early cue to review and potentially adjust hedges.

Another important signal is the shape of the yield curve. Under normal conditions, long-term interest rates are higher than short-term rates, reflecting expectations of future growth. But when short-term rates exceed long-term rates—a phenomenon known as an inverted yield curve—it has historically preceded recessions. While not a perfect predictor, this pattern warrants caution. Investors might respond by increasing allocations to defensive assets or tightening their risk exposure, not because a downturn is guaranteed, but because the odds have shifted.

Rising margin debt is another under-the-radar warning. When investors borrow heavily to buy stocks, it indicates overconfidence and increased financial leverage across the market. High margin levels can amplify downturns, as forced selling during a drop leads to cascading losses. Monitoring this data, available through regulatory reports, helps identify periods when the market is more vulnerable to shocks. It’s not a reason to panic, but a signal to ensure that risk controls are in place.

Corporate earnings trends also offer valuable insight. A broad decline in earnings quality—such as shrinking profit margins, rising inventories, or weakening guidance—can foreshadow broader economic challenges. These developments may not immediately affect stock prices, but they erode the fundamentals that support valuations. When combined with other signals, they strengthen the case for proactive risk management. The key is not to act on any single indicator, but to watch for convergence—a cluster of subtle warnings that together suggest a shift in market conditions.

Smart Tactics That Adapt to Timing

Given the uncertainty of timing, the best hedging strategies are those that offer flexibility. Rigid, all-or-nothing approaches often fail because they assume perfect foresight. Instead, adaptive tactics allow investors to respond to evolving conditions without overcommitting early. One such method is dynamic asset allocation, where the mix of stocks, bonds, and cash is adjusted based on market indicators. For example, as valuations rise and volatility increases, an investor might gradually shift from equities to bonds or short-term Treasuries, reducing exposure without abandoning growth entirely.

Another flexible tool is the collar strategy, which combines a long stock position with a protective put option and a covered call. This setup limits both downside and upside, but at a lower net cost than buying puts alone. It’s particularly useful when an investor wants to maintain exposure but reduce risk during uncertain periods. Because the call option generates income that offsets the put’s premium, the overall cost is minimized. This makes the collar a practical choice when timing is unclear but caution is warranted.

Tactical cash positioning is another underappreciated tactic. Holding a modest portion of the portfolio in cash or cash equivalents provides liquidity and optionality. It allows investors to act when opportunities arise, whether that means buying undervalued assets or reinforcing hedges. Unlike complex derivatives, cash carries no counterparty risk and doesn’t decay over time. It’s a simple, reliable form of protection that works in any environment.

For those with international exposure, currency-hedged ETFs offer a way to neutralize exchange rate risk without constant monitoring. These funds automatically adjust for currency fluctuations, providing stability for long-term investors who want to focus on asset performance rather than forex movements. While not a solution for every portfolio, they are a valuable tool when foreign currency volatility threatens to overshadow underlying returns.

Common Mistakes That Turn Protection into Loss

Even well-intentioned hedging can backfire when basic principles are ignored. One of the most frequent errors is over-hedging—protecting more than necessary. Some investors, fearing loss, end up hedging their entire portfolio, effectively neutralizing any potential for growth. This defeats the purpose of investing altogether. A hedge should reduce risk, not eliminate return. The goal is balance: enough protection to weather storms, but enough exposure to benefit from recoveries.

Another costly mistake is the use of leveraged products. Inverse or leveraged ETFs promise amplified protection, but they are designed for daily use and can produce misleading results over longer periods. Due to the mechanics of daily rebalancing, these funds can lose value even in flat or slightly declining markets. Investors who hold them for weeks or months may be shocked to find that their hedge has eroded significantly, leaving them worse off than if they had done nothing.

Misunderstanding expiration terms is also common. Options, for example, have a limited lifespan. A put option that expires before a market drop offers no protection at the moment it’s needed. Investors must pay attention to contract dates and be prepared to roll positions forward if necessary. Failing to do so can create a false sense of security. Similarly, ignoring the cost of carry—the ongoing expense of maintaining a hedge—can lead to unnecessary drain on portfolio returns.

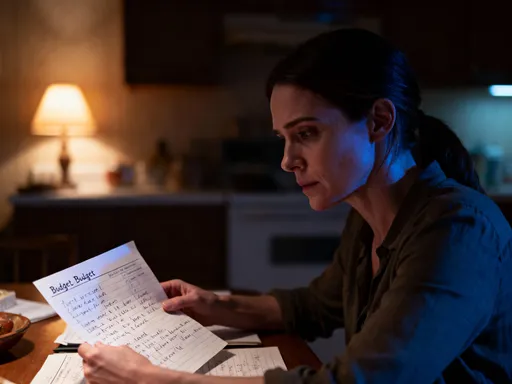

Perhaps the most damaging error is allowing fear to dictate strategy. Hedging should be a rational, planned component of portfolio management, not an emotional reaction to headlines. When decisions are driven by anxiety, investors often act too late, pay too much, or choose inappropriate tools. The antidote is discipline: a clear framework for when and how to hedge, based on objective criteria rather than sentiment.

Building a Sensible Hedging Mindset

Ultimately, successful hedging is less about tactics and more about mindset. It requires a long-term perspective, emotional discipline, and a commitment to consistency. The most effective investors don’t wait for crisis to act; they treat risk management as an ongoing process, regularly reviewing their exposure and adjusting as conditions change. They understand that perfect timing is unattainable, but prudent preparation is always possible.

This mindset begins with clarity of purpose. Every hedge should serve a specific role in the portfolio—whether it’s protecting a retirement nest egg, preserving capital for a future goal, or reducing volatility to improve sleep at night. When the objective is clear, it’s easier to choose appropriate tools and avoid unnecessary complexity. Simplicity, transparency, and alignment with personal financial goals are the hallmarks of a sound strategy.

Continuous monitoring is equally important. Markets evolve, and so should risk controls. Regular check-ins—quarterly or semi-annually—help ensure that hedges remain relevant and cost-effective. This doesn’t mean constant tinkering, but thoughtful evaluation in light of new data. Adjustments should be based on changing fundamentals, not fleeting emotions.

Finally, the sensible hedging mindset accepts uncertainty as a constant. No strategy can eliminate all risk, nor should it try. The goal is not to predict the future, but to build resilience. By focusing on what can be controlled—costs, timing, diversification, and discipline—investors can protect their wealth without sacrificing peace of mind. In the end, the best shield isn’t one that blocks every blow, but one that allows you to keep moving forward, no matter what the market brings.